- Sales & Support

- +61 2 4225 9698

- [email protected]

Strategies for Guiding Effective Literacy Teaching – Part 1

September 10, 2020

Strategies for Guiding Effective Numeracy Teaching – Part 3

September 16, 2020Strategies for Guiding Effective Literacy Teaching – Part 2

By: Renaissance Professional Development Team

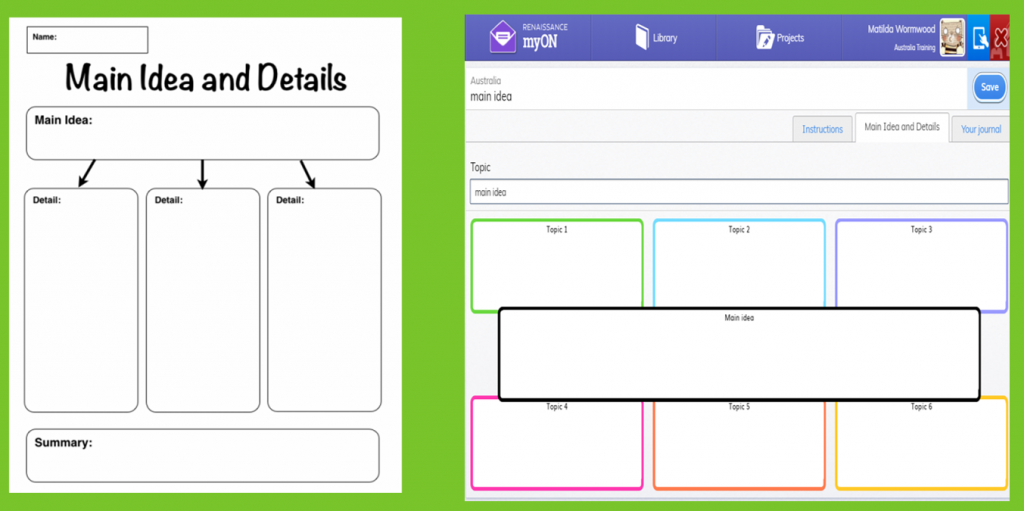

Welcome to the second post in our series on literacy and numeracy strategies, exploring three more literacy strategies that we’ve seen being used in schools that we work with and consider how they might work with Renaissance solutions.

Chunking

When we discussed scaffolding, we made mention of another strategy – chunking. Chunking involves breaking down difficult text into more manageable pieces and having students rewrite these “chunks” in their own words. Cognitive science research tells us that breaking content into logical segments makes the information easier to process, to learn, and to remember. Chunking helps students identify key words and ideas in text, it develops their ability to paraphrase, and makes it easier for them to organize and synthesize information in the text.[1]

To help students move from reading the text to paraphrasing the text, ask them to first identify and define the key words found in that chunk of text they are working with. By the end of the chunking activity, students should have a paraphrased version of the original text.

Chunking doesn’t mean simply breaking up text into smaller pieces. It means breaking them up into related, logical, meaningful, and sequential segments. Sometimes teachers chunk the text in advance for students (type of scaffolding), especially if this is the first time students have seen the text. Other times, teachers may ask students to chunk the text themselves, or students can work on chunking texts with partners or in groups. Depending on students’ reading level, the lengths of chunks can vary. A stronger reader can often work with bigger chunks of text, where a struggling reader might work with smaller chunks.

It is helpful to have students record information about each “chunk” in a graphic organiser, which you may want to prepare in advance. The paraphrased text in the graphic organiser can be used to evaluate students’ understanding and reading ability. There are numerous graphic organisers available in myON that all serve different purposes like summarising, discovering new knowledge or activating prior knowledge. These templates in myON to assist students’ comprehension of a text that they have just read digitally in the platform.

Setting Goals

In 2009, John Hattie conducted research on the effect size of various influences on student achievement.[2] Scenarios in which students had learning goals vs not having any and having appropriately challenging goals had notable effect sizes.

Goals can operate in the classroom at various levels. A clear learning intention that clarifies what success will look like at the end of the lesson actually helps plan learning activities and more importantly, helps students understand what they need to do. There are plenty of ways to demonstrate this in the classroom and if we look at the strategy of Blackboard Configuration, it is underpinned by the requirement of a lesson objective and then optional additions like a Do Now Activity, Vocabulary, Lesson Agenda or an Exit Ticket.

Moving to individual student goals, we need to set challenging goals, rather than ‘do your best’ goals but critically we need to be aware of student starting places. Goals should be differentiated based on ability and achievable for students of varying literacy levels and characteristics, ideally having a firm base in assessed student needs. After all, assessment provides teachers with evidence of prior learning, and the information they need to set goals that offer each student the appropriate level of stretch or challenge.

Consider reading, if we were to set the same goal for every student in our class, e.g. everyone needs to read one book a week, that suits the students at lower literacy levels who can power through shorter books, whilst students dedicating more time and effort to reading longer, more challenging texts will not necessarily meet this weekly goal. By setting challenging, diverse goals, the teacher develops and maintains a culture of high expectations in line with each student’s level of ability.

Accelerated Reader measures books for difficulty and length, allocating points to each title in the program. When a student takes a quiz, they accumulate points based on their score and these count towards a goal or target which has been developed by the program based on the student’s Star Reading assessment score. The screenshots below display the way younger and older students are able to view their progress. As a result, students are presented with a reading goal that is not unrealistic, but rather differentiated to their individual reading ability and frequency.

Worked Examples

When looking at many of these strategies, we should be aware that the information outlined is in no way a complete or comprehensive discussion but rather a platform for ideas and a starting point for further investigation. One concept that underpins many of the literacy and numeracy strategies in the classroom is cognitive load theory.

“Cognitive load” relates to the amount of information that working memory can hold at one time. Sweller stated that since working memory has a limited capacity, instructional methods should avoid overloading it with additional activities that don’t directly contribute to learning.[3]

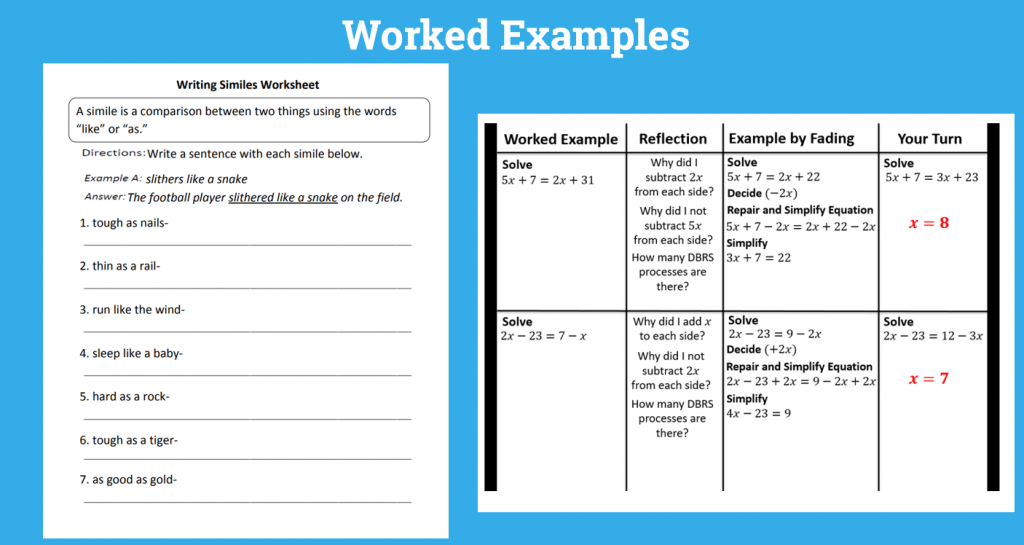

If we take this principle and attempt to demonstrate it in the classroom, a brilliant example would be facilitating worked examples. A worked example is a clear demonstration of the steps required to complete a task or solve a problem. By scaffolding the learning, worked examples support skill acquisition and reduce the cognitive load for learners. Usually, the teacher presents a worked example to students and explains each step.[4] Later, students can use worked examples during independent practice, and to review and embed new knowledge. Anecdotally, worked examples require less time to process than a conventional problem, ultimately leading to students processing similar tasks more quickly.

Using worked examples without proper consideration in the classroom has been determined to ineffective when compared to other strategies that direct attention appropriately and allow for the right amount of cognitive load. This can be managed with preparation, explicit scaffolding and chunking of tasks as displayed in the examples below.

If you’re using any of these strategies in the classroom already and would like to share your experiences, or if you’ve got some other ideas you’d like the Professional Development team to explore, then drop us a message or a comment. Stay tuned for our next post on numeracy strategies for effective teaching!

References:

[1] http://journal.uin-alauddin.ac.id/index.php/Eternal/article/view/2419

[2] https://visible-learning.org/hattie-ranking-influences-effect-sizes-learning-achievement/

[3] https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/cognitive-load-theory.htm

[4] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220973.2012.727884